Inauguration 13th September 2013 h. 20.00 at Si-Fest di Savignano sR. until September 15th.”

Species of spaces in a bottle

by Claudio Ballestracci

Georges Perec’s Species of Spaces begins like this: “The subject of this book is not exactly emptiness, but what there is around or inside it”. Immediately afterwards comes the reference to figure 1, with which the book opens, i.e. the “Map of the ocean” (inevitably empty), taken from The Hunting of the Snark by Lewis Carroll

And Perec concludes: “Space dissolves like sand running through your fingers. Time takes it away, leaving me with only a few shapeless shreds … “. He seems to echo the words of Goffredo Parise: “Having travelled a great deal around the world, I felt dissolve between my fingers and become dust something that is the essential core of human persons, i.e. their territory”.

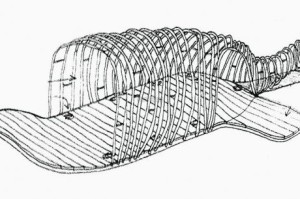

In the wake of these and other suggestions I’d like to think that space is now the city square from which a bottle emerges, as on the surface of the ocean. The large bottle was not there, just as the words of Perec were not there before they left a trace on the map, creating, with their meticulous descriptions, worlds and spaces. The appearance of the bottle-auditorium is an idea first sketched on a piece of paper, discussed on several occasions, redesigned in the form of working drawings, built with the help of a group of people, disassembled and reassembled several times, and taking shape, each time, in a different place. It is an invention, a drawing in a town square that becomes a highly temporary living space. The town square is like Perec’s sheet of paper, on which we draw a kind of fading species of space, because after three days it will disappear again leaving us with the idea of that place, another possible idea of space to bear witness to the message that is contained in the title of Perec’s book, the inspiration behind the 2013 photography festival, as well as in our invention, an ethical monument halfway between a dream and a protest.

There are three themes: space, which never exists because it continuously dissolves and is recreated; the bottle, which, by its nature, gives shape to the space around it when it encloses a space; and lastly water, that seems the perfect metaphor for every kind of space since it takes the form of what it contains, circumscribing it in space. But as soon as that form is broken or dissolves, it also flows away, assuming new forms and occupying new spaces.

In Tao te Ching by Lao Tzu, we read: “We join together the spokes of a wheel, but it is the hole in the middle that propels the cart. We give shape to clay to create a vase, but it is the empty space inside that holds what we want. We build a house with wood, but it is its interior space that makes it liveable”.

Water belongs to everyone, ethics and poetry

Empedocles could become the patron saint of ecologists. The parallel is striking: precisely those aspects of nature that ecologists are now having to defend, he had already identified at the beginning of Western philosophy as fundamental elements of the world. For him the Cosmos consisted of water, earth, air and fire, and these are the four elements that ultimately unite the grandiose and intricate multiplicity of natural phenomena. Is it not perhaps happening today that, just when the four elements are continually exposed to the danger of poisoning, we are beginning to come up against this ancient truth? Only under the threat of self-destruction have we rediscovered the four elements as sources of life, something that Empedocles had already understood without the help of this lesson.Wolfgang Sachs, Preface to the Italian edition of Ivan Illich, H2O and the Waters of Forgetfulness, Macro Edizioni, Umbertide (PG) 1988

Empedocles could become the patron saint of ecologists. The parallel is striking: precisely those aspects of nature that ecologists are now having to defend, he had already identified at the beginning of Western philosophy as fundamental elements of the world. For him the Cosmos consisted of water, earth, air and fire, and these are the four elements that ultimately unite the grandiose and intricate multiplicity of natural phenomena. Is it not perhaps happening today that, just when the four elements are continually exposed to the danger of poisoning, we are beginning to come up against this ancient truth? Only under the threat of self-destruction have we rediscovered the four elements as sources of life, something that Empedocles had already understood without the help of this lesson.Wolfgang Sachs, Preface to the Italian edition of Ivan Illich, H2O and the Waters of Forgetfulness, Macro Edizioni, Umbertide (PG) 1988

A bottle, half emerging from the ground, pitching, bobbing on the surface, carrying a message. The horizontal water line is slightly oblique, and the bottle seems to want to sink once again, seems to want to be shipwrecked despite its new appearance. This is the fate of messages in bottles: they are thrown into the sea in the hope that someone will find them. They do not always arrive at their destination, and sometimes plunge to the depths or lie neglected for years, decades. However, the message in the bottle is almost always urgent, the iconic SOS, a call for help, where the means adopted contains an obvious anomaly, a contradiction that seems to echo virtual networks or global communication.

The echo and the proliferation of messages, albeit for noble causes, often conceals a pitfall, that of going unnoticed in the immense, uniform media machine.

The image of something discarded, left over, is evident: a plastic bottle abandoned like so many others, but slightly out of scale, as disproportionate as the message inside, as outsized as the issue it aims to tackle, a problem as big as the ocean. These initial observations seem to suggest a tendency towards gigantism, sculptural hypertrophy as a way of showing off and getting noticed. But the creative process chooses other paths.

The theme to focus on when creating a dedicated work is clear: water and, perhaps, the alchemical effects of such a precious fluid encourage a transfer of knowledge that may confuse the origin of the idea.

Some notions on its genesis can however be deduced from the meeting between its creators: an atypical architect, who has traded in his pencil case for a tool-bag, and nourishes a sincere aversion to waste, concrete and town plans; an author of night tales and organiser of underground musical events; a musician dreamer with his feet in a pot of earth from Romagna and silicon; a blue-collar sculptor and props man hopelessly inclined to experimentation.

The ink required to draw the piece is provided by the meeting of such different characters, but united by a shared love for the workshop, for experimentation in the field, for leaving back on the office desk the more “rational” aspects, those related to texts and concepts, and instead aiming to infuse poetry in work through one’s hands.

The plastic bottle is the symbol chosen for the work, since it is the primary domestic object that makes us immediately think of water as an element essential to life, but also of its consumption and the inevitable economic and environmental implications that this entails: the industrial exploitation of a common asset, misuse and waste, the disposal of plastic waste, pollution, the disfigurement of the landscape. “I’m talking,” writes Illich, “about the torpor that envelops individuals when they lose the sense necessary to imagine the substance of water, not its external forms, but the deep substance of water.”

In the city of Kassel a German baroque prince has built himself a castle surrounded by English gardens which solicit the waters to betray all they can tell. Water is not only meant to reveal itself to the eye and the touch but to speak and sing in seventeen different registers. Thus dream waters mumble and ebb and swell and roar and trickle and splash and stream and dally, and they wash you and can carry you away, they can rain from above and well up from the depths: they can moisten you or just wet…Ivan Illich, In the Mirror of the Past 1992

In the city of Kassel a German baroque prince has built himself a castle surrounded by English gardens which solicit the waters to betray all they can tell. Water is not only meant to reveal itself to the eye and the touch but to speak and sing in seventeen different registers. Thus dream waters mumble and ebb and swell and roar and trickle and splash and stream and dally, and they wash you and can carry you away, they can rain from above and well up from the depths: they can moisten you or just wet…Ivan Illich, In the Mirror of the Past 1992

The outsized size is consistent with its function as an auditorium large enough to accommodate the public; a mystical basin for four fountains activated by the public themselves, who here become virtuosos and musicians by chance.

The fountains issue their jets of water continuously, spraying into circular tanks to emphasise the waste of water, and can only be stopped by the gesture of blocking the flow with their hands, while in its place, sound gushes out. Consequently, each fountain turns out to be a stringed instrument – first and second violin, cello and viola – following a changing score, at times energetic, then unpredictably lively, then quiet and dreamy. And the visitor is disposed to discover the qualities of their own instrument, to find harmony with the others, to personalise the collective performance. The musical pieces played by the fountains, specially conceived by Marco Mantovani, are suited to an infinite number of sound combinations, and the resulting string quartet is never the same. In other words, the score is complete only if the public is in harmony. And the water is safe.

A different, equally important degree of interaction took place in the construction phase, when the authors, guests in the town of Périgueux, worked together with school-children, associations and volunteers to collect and process around 3000 discarded PET bottles, used to coat the giant bottle. In this phase, numerous workshops were organised, involving citizens in a vast project aimed at heightening awareness of the issues, both social and ecological: of making people aware of the environmental costs involved in our lifestyle, reducing the production of waste, becoming responsible for differentiated collection and creative in using waste material.

In that period, the announcement of a referendum asking the citizens for their opinion on the privatisation of public water, in Italy, inspired us to strongly express our views, changing the name of the installation while work was in progress: circumstances took over and we decided to put a message in the bottle, stripped of metaphor, direct, even didactic.

Water belongs to Everyone thus became essentially a work to awaken the public: restoring to water the dignity of a common asset in relation, translating it into a poem of the senses that manages to communicate without being filtered by reason.

A huge bottle now floats on the surface of the earth, on the skin of the tarmac, tracing courses on the road map instead of nautical charts.

Creators of the interactive work “Water belongs to everyone”

Giulio Accettulli, Claudio Ballestracci, Manolo Benvenuti

Original music by Marco Mantovani

Designed in Rimini as part of the Ambiente Festival 2011 and created in Périgueux (France) for the festival Art et Eau 2011, the Bottle arrived in Rimini in 2012, hosted by the festival Armonie d’acqua for the Centenary of the Acquedotto Riminese and the World Water Day. It continued on its journey, surfacing in front of the theatre in Noisy Le Grand (France) for the festival Fontaines en scène and then in Geneva (Switzerland) for the Fêtes de Genève, inspired by the theme of water.

« L’Acqua è di tutti Water belongs to everyone, the project »

Settembre 2013 – In piazza Borghesi, nell’ambito del SI Fest #23 intitolato Specie di spazi, la Bottiglia articola la propria riflessione sullo spazio liquido: un ambiente né chiuso né aperto, capace di astrarre dal contesto chiunque partecipi e coinvolgerlo, per qualche momento, in intense relazioni estetico-ricreative. Un vuoto denso di umanità. Un pieno che defluisce e rifluisce come il fascino primordiale della condivisione

Settembre 2013 – In piazza Borghesi, nell’ambito del SI Fest #23 intitolato Specie di spazi, la Bottiglia articola la propria riflessione sullo spazio liquido: un ambiente né chiuso né aperto, capace di astrarre dal contesto chiunque partecipi e coinvolgerlo, per qualche momento, in intense relazioni estetico-ricreative. Un vuoto denso di umanità. Un pieno che defluisce e rifluisce come il fascino primordiale della condivisione

[…] Fontaines en Scène 2012 SI-Fest 2013 Species of spaces […]